Project to strengthen the collective rights of land and territories of the Indigenous Peoples of Panama

Completed

From:

30/06/2015

To:

30/04/2017

Partners:

National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama (COONAPIP)

Fiscal sponsor: Program for Social Promotion and Development (PRODESO)

Associates:

Government of Panama: National Land Administration Authority (ANATI)

Ministry of Environment

National Commission for Political and Administrative Limits

National Geographic Institute “Tommy Guardia”

Rainforest Foundation US

Traditional authorities (congresses and councils) of participating indigenous territories

Stakeholders:

Indigenous Peoples, communities and their participating traditional authorities

COONAPIP

National Land Administration Authority (ANATI)

National Environmental Authority (ANAM)

National Commission for Political and Administrative Limits

National Geographical Institute “Tommy Guardia”

Academic and civil society organizations

While Panama’s laws on indigenous rights are progressive, implementation lags far behind. With Tenure Facility support, COONAPIP capitalized on the current Government’s commitments to indigenous rights and favourable rulings of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the Panama Supreme Court.

To read a brief overview of Panama, click here.

For a timeline of land and forest rights in Panama, click here.

"COONAPIP was formed years ago to strengthen indigenous struggles, in particular for territories. It is essential that our brothers respect the land. It is our dream. Comarcas have been achieved, Law 72 has been achieved, but there has been no follow-up. Through this project, we can achieve visibility and be heard. The project opened a path. A road was cut. It is possible now to sit down and talk to the government. "

- Marcelo Guerra, President of COONAPIP

Project Overview

COONAPIP advanced titling of 231,328 hectares.

Goal

To consolidate and protect the collective rights (land, forest and water) of Panama’s Indigenous Peoples.

Objectives

- Capitalise on existing opportunities with the Government of Panama to accelerate processes of land titling, registry, and conflict resolution, and strengthen governance of indigenous territories.

- Develop institutional capacity to support the full exercise and protection of indigenous territorial rights.

Actions

- Strengthen COONAPIP’s capacity to provide legal services in support of Indigenous Peoples’ full enjoyment, exercise, and protection of their rights to land, water, and forests.

- Train traditional indigenous authorities on priority issues of indigenous rights and develop permanent and continuous access to legal advice and services in support of the advancement of indigenous rights and territorial governance.

- Support titling and registration of the Collective Territories of Bajo Lepe and Pijibasal.

- Advance legal and administrative processes for the titling of the Territory of Maje Embera Drúa.

- Advance the titling processes in other communities.

Results

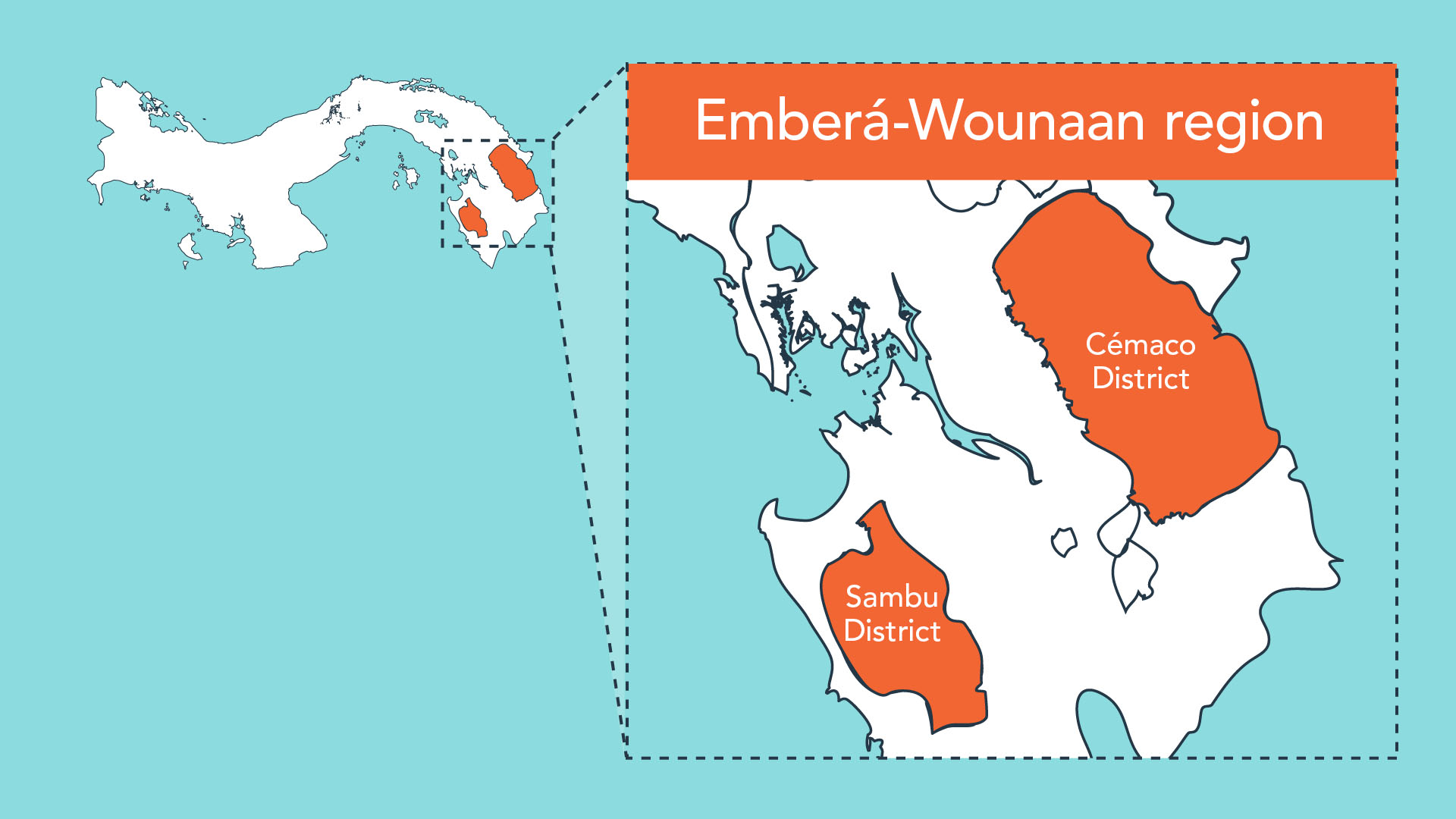

- Advanced titling of 231,328 hectares in six territories, resolved conflicts, defined boundaries and established official plans: Bajo Lepe, Pijibasal, Maje Emberá Drua, Rio Congo, Bribri, and Tagarkuny.

- Resolved 18 tenure conflicts affecting 223,260 hectares in four territories: Bajo Lepe, Pijibasal, Bribri y Tagarkunyala.

- Supported titling and registration of the Collective Territories of Bajo Lepe and Pijibasal, however, title not yet granted because Ministry of Environment has not approved due to overlap with land claimed by protected area.

- Created ‘Clinica Juridica’—a legal clinic that supports land titling.

- Clarified the steps for titling indigenous lands.

- Trained 252 women, men and young people in indigenous rights and law.

- Initiated discussions to establish a diploma at the University of Panama’s Faculty of Law to broaden understanding of Indigenous Peoples’ legal rights under national and international law.

"We have been fighting the titling of our territory for more than 40 years. In the last year, with the support of COONAPIP’s PDCT project, we have advanced more than in the previous 40 years."

- Lazaro Mecha

, Regional chief, Majé Emberá Drüa collective territory

Impact

- Strengthened COONAPIP’s administrative and technical skills and capacity to title indigenous lands.

- Built momentum for faster and more efficient titling by raising awareness of Indigenous Peoples’ rights among government authorities, building relationships among relevant institutions and increasing the confidence of Indigenous Peoples in their power to effect change.

- Positioned Indigenous Peoples to protect land, forest and water, and improve livelihoods, thereby contributing to global climate change and development goals.

- Demonstrated new methods that indigenous communities can use to resolve conflicts among themselves and with government, investors, immigrants, and settlers.

Lessons learned

- Greater inclusion and equity for women and girls in the titling processes remains a challenge.

- A detailed roadmap for titling is needed for all parties to understand the roles and responsibilities of each actor at every step.

- Close working relationships between COONAPIP and government authorities are essential as evidenced by success of joint teams for preparing and verifying the titling application documents.

- A strong Tenure Facility Country Focal Point for the entire project would have been valuable.

- The windows of opportunity for the titling of indigenous territories can be very short, remaining open for only a few months and then closing abruptly due to government’s political considerations, without specific changes in a country’s relevant laws or the larger political and economic context.

- A forward-looking legal framework, particularly in countries like Panama is not sufficient. The current framework can be complex, and the contradictions or inconsistencies within the various rules that regulate titling processes can be hard to understand, and these discrepancies can become “bottlenecks.”

- A monitoring, assessment and learning system or approach must be tailored to a particular organization because organizations are different from each other. This suggests that in the process creating the Tenure Facility monitoring, assessment and learning system, the “bottom-up” approach must be considered through paying more attention to local experience development, and seeing how these local experiences can feed into a system which applies to all Tenure Facility activities.

Marcelo Guerra

COONAPIP president

marceloguerra75@hotmail.com

Manuel Martinez

Project Coordinator

manuelmartinezv@gmail.com

Links

coonapippanama.org