2024-09-05

Community forest concessions are a groundbreaking initiative in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) which give communities greater control over their traditional territories. Known by the French acronym CFCL, these concessions are parcels of forests that are collectively managed and owned, for evermore, by indigenous and local communities.

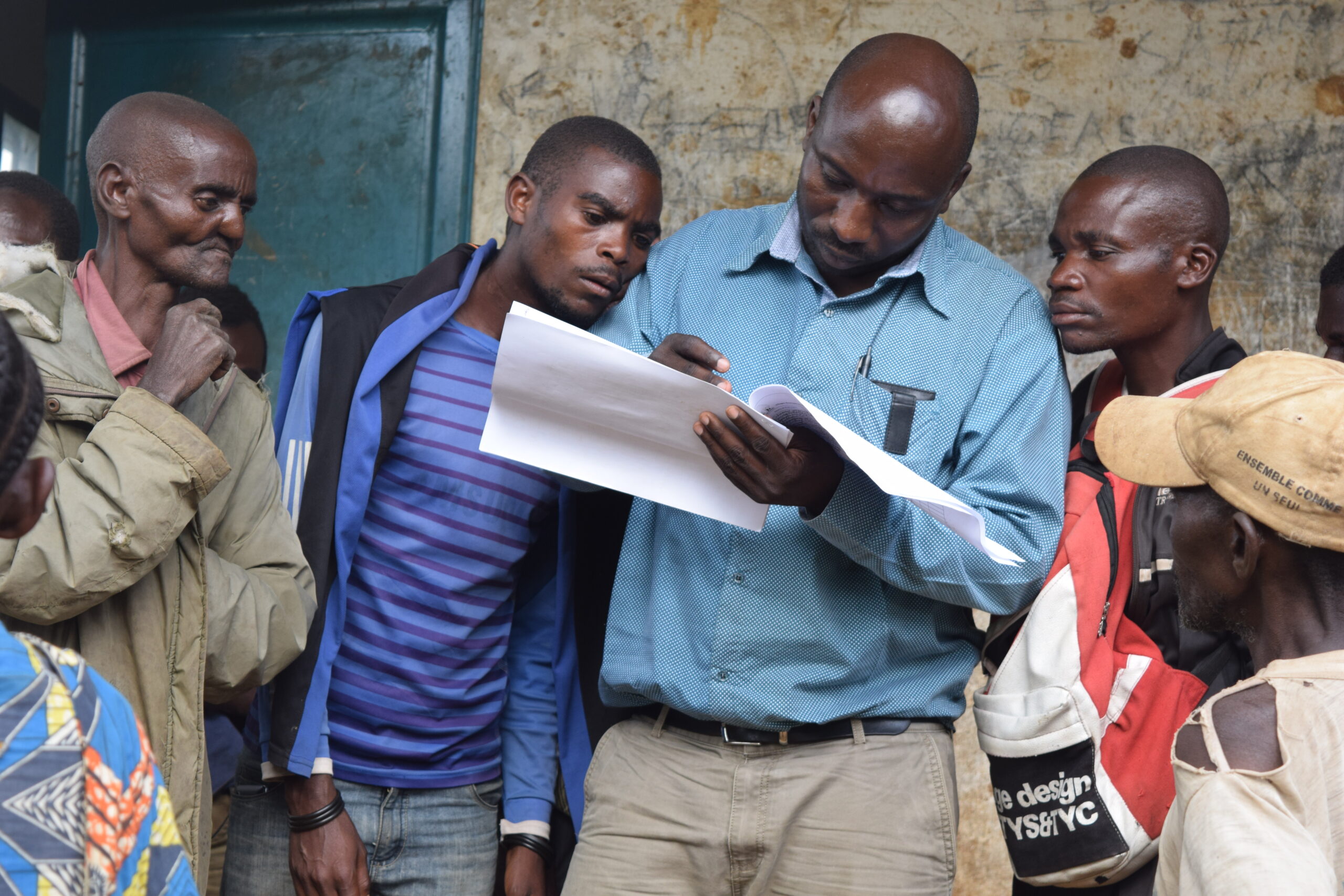

In South Kivu, a province in western DRC that has seen rights abuses, violent clashes and displacements over the years, 23 communities so far have been granted CFCLs, marking a significant milestone there in forest conservation and local governance. These titles, collectively held and protected under legal frameworks, ensure that the communities can access and use their ancestral lands as well as prevent others from exploiting it without their consent.

Tenure Facility spoke with Dominique Bikaba, the executive director of Strong Roots Congo, which was recently awarded a UN Human Rights Prize, about his organisation’s work with CFCLs in South Kivu. He explained how CFCLs work, why they came about and how communities are preserving their cultural heritage and ensuring their well-being in one of the most important ecosystems in the world. Below are excerpts from the interview, edited and condensed for clarity.

Q: What do these forestry concessions means for the communities in South Kivu?

A: The recent titling is incredibly significant for them. They have been tending to these lands for centuries, based on their customs and regulations. However, they never had full control as the government could reallocate the land at any time as protected areas or concessions for mining or logging.

With CFCLs, which are collectively held, it means no one within the community can sell the land, not even the chief. What’s more, the government can no longer grant overlapping titles on these lands due to constitutional and legal protections. This means the land is now secure from being allocated to other users, whether by the government or other entities.

If someone wants to take resources from the forest, they can no longer get direct authorisation from the government and bypass the community. They must start negotiations with the community first and reach an agreement with them. Only after this can a company seek government permission and then pay the necessary taxes. This ensures that the community retains control and benefits from the resources.

Q: Why did the government set up this program?

A: The government wants to reduce poverty, promote rural and community development, and improve living conditions through this. They also believe that communities will manage the resources sustainably and preserve the forests for future generations. If a community fails to preserve the forest and destroys it, the government has the right to revoke the title, but this would require a lengthy process.

Q: You mentioned how even a community chief cannot make decisions alone on CFCLs. How are these structured then within the community?

A: The community governance structure involves multiple bodies. There are 46 tools required to apply for a local community forest concession, which include local governance and management structures. The community assembly is responsible for consultations and elections. There is a governance body, a management body, and a council of elders to handle conflicts, especially those related to customs and traditions.

CFCLs also require a simple management plan, revised every five years, that guides land use and ensures sustainability. (Strong Roots Congo uses) technology and regular visits to monitor land use, checking for changes due to things like immigration or mining. This plan changes over time, reflecting the community’s commitment to preserving the forest for both personal and collective benefits.

"The relationship between the communities and nature can be summarised as healing, peace, and life. The community's well-being is deeply connected to the forest."

Q: What role does the partnership with Tenure Facility play in this process?

A: Tenure Facility has been instrumental in our journey. After my fellowship with Conservation International in 2011, I realised the need for a legal framework to recognise community forest management. In 2014, DRC passed a law allowing communities to govern their lands. In 2019, Tenure Facility provided seed funding to officially launch our community forestry initiative in South Kivu. This support helped us bring together government officials, traditional leaders, and civil society to start the process.

Q: Can you share more about the challenges and successes you’ve encountered?

A: One major challenge was getting continued funding after our initial success. Despite setbacks, we persevered with support from other organisations. In 2022, we achieved a significant milestone by obtaining 13 CFCLs in South Kivu. This success demonstrated the power of community engagement and the trust we built over the years.

Q: How do cultural customs influence a community’s relationship with their land and resources?

A: Cultural customs are deeply ingrained in the community’s identity and governance. For instance, there are strict regulations about privacy and respect for women, which, if violated, result in severe punishments according to their customs. These customs are not just rules but are vital for maintaining the power dynamics and societal structure. The land and forest are integral to their way of life and their customs, and without the forest, their cultural identity would be at risk.

Q: Can you elaborate on the relationship between the communities and nature, especially given the recent disruptions and violence in the region?

A: The relationship between the communities and nature can be summarised as healing, peace, and life. The community’s well-being is deeply connected to the forest. Protected areas have often failed in Africa because conservation efforts have tried to separate humans from nature. But humans are part of nature, and separating them only leads to the destruction of both.

The poverty seen around protected areas is often mental rather than resource-based. When communities are separated from their forests, they feel impoverished regardless of their material wealth. The Western concept of poverty does not align with the African understanding, which is more about access to natural resources and cultural heritage.

"They have been tending to these lands for centuries, based on their customs and regulations. However, they never had full control..."

Q: How do traditional practices help in preserving nature and biodiversity?

A: Traditional practices have long been the cornerstone of biodiversity conservation in these communities. Documentation of these practices, like the ones by the pygmies around Kahuzi-Biega National Park, shows how indigenous knowledge has sustainably managed the environment for centuries. However, threats such as religion, colonialism, modernism, and especially war, have challenged these practices. Despite these challenges, the communities continue to prioritise their cultural values and traditional knowledge in their conservation efforts.

Q: Can you give examples of how traditional knowledge is applied in everyday life for these communities?

A: Traditional knowledge is deeply embedded in daily life. For example, my own experience with my pygmy caretaker illustrates how nature and cultural practices provide emotional and spiritual support. Spending time in the forest, following customs, and engaging in traditional rituals offer a sense of peace and healing. This connection to nature helps maintain mental health and resilience, which is crucial for surviving the numerous adversities they face.

Q: What are the broader implications of losing traditional knowledge and practices due to war and modern disruptions?

A: Its loss has profound implications. These practices are essential for maintaining ecological balance and cultural identity. The destruction of sacred sites and the displacement of communities result in the loss of invaluable knowledge that cannot be easily recovered. Future generations, born in refugee camps or disconnected from their cultural heritage, will lose touch with these traditions, leading to a diminished capacity to preserve the environment and cultural identity. This loss will be costly for both the communities and the broader efforts in conservation and sustainable living.

Q: How do you see the future of community forestry in your region?

A: The future looks promising. Our focus is on maintaining the integrity of these forests while ensuring the community’s benefit. The engagement and trust we’ve established are key to our success. We continue to work towards integrating traditional knowledge with modern conservation practices, ensuring that these forests remain a vital resource for future generations.

Articles