2024-10-02

By Jeremy Gaunt

There are some quite staggering numbers that underline the importance of Indigenous Peoples to the global environment: they manage or hold tenure over 25 percent of the world’s land surface, including 36 percent of the world’s remaining intact carbon-soaking forests. Within that, immeasurable biodiversity thrives.

The import of this has not been lost on world governments and foundations. At the 2021 COP26 in climate summit, a group of them* committed $1.7 billion through to 2025 to support the land tenure rights and forest guardianship capabilities of Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities.

But a lack of trust and understanding means only a small amount of this is coming through properly to Indigenous Peoples on the front line.

Only about 7 percent of disbursements from the $1.7 billion so far have made it to Indigenous organisations, the rest going to governments and outside NGOs.

So, there is an immediate need for more of the money to reach those who best know how to use it, and to prepare for a second round of funding from philanthropies, bilaterals and multilaterals at next year’s COP30.

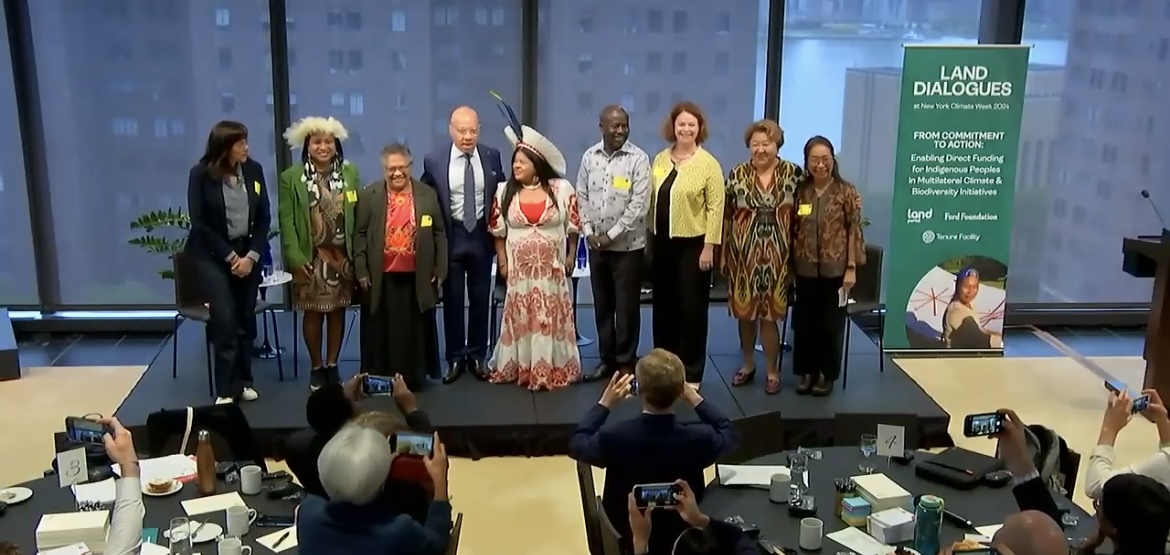

That was the main message at the September 23 Land Dialogues held as part of New York Climate Week, coinciding with the United Nations General Assembly meeting.

“When Indigenous Peoples and local communities have legally recognised and enforced rights, they protect their lands,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, which hosted the meeting and co-sponsored it with the Land Portal and Tenure Facility. “(But) high quality funding and sufficient quantity of resources are imperative.”

"When Indigenous Peoples and local communities have legally recognised and enforced rights, they protect their lands.(But) high quality funding and sufficient quantity of resources are imperative."

Panellists primarily put this down to two factors: the conventional financial system and trust.

“The predominant funding and financial ecosystem is very rigid and is made of rules that are almost impossible to reach for Indigenous People-led funds,” said María Pía Hernández, regional manager of the Mesoamerican Territorial Fund, which provides direct financing to communities from southern Mexico to northern Costa Rica.

Reporting requirements for governments, international organisations, and philanthropic entities do not always sit neatly with organisations and communities that have had limited exposure to these financial systems in the past.

Donors have, in the past, said that they cannot just hand money over without following their embedded checks and balances, which can hit barriers when it comes of Indigenous-led entities. This is particularly the case with large multinational development banks, to which Hernandez was referring.

Some donors are beginning to adjust. Stephanie Speck, head of communications at the $15 billion Green Climate Fund (GFC), noted that the GCF is seeking to improve the efficiency of financing. This included moving from a project-driven approach to a more regional one. The fund, which is not specifically focused on Indigenous Peoples but has an Indigenous Peoples Advisory Board, is also planning to speed up its donor processes.

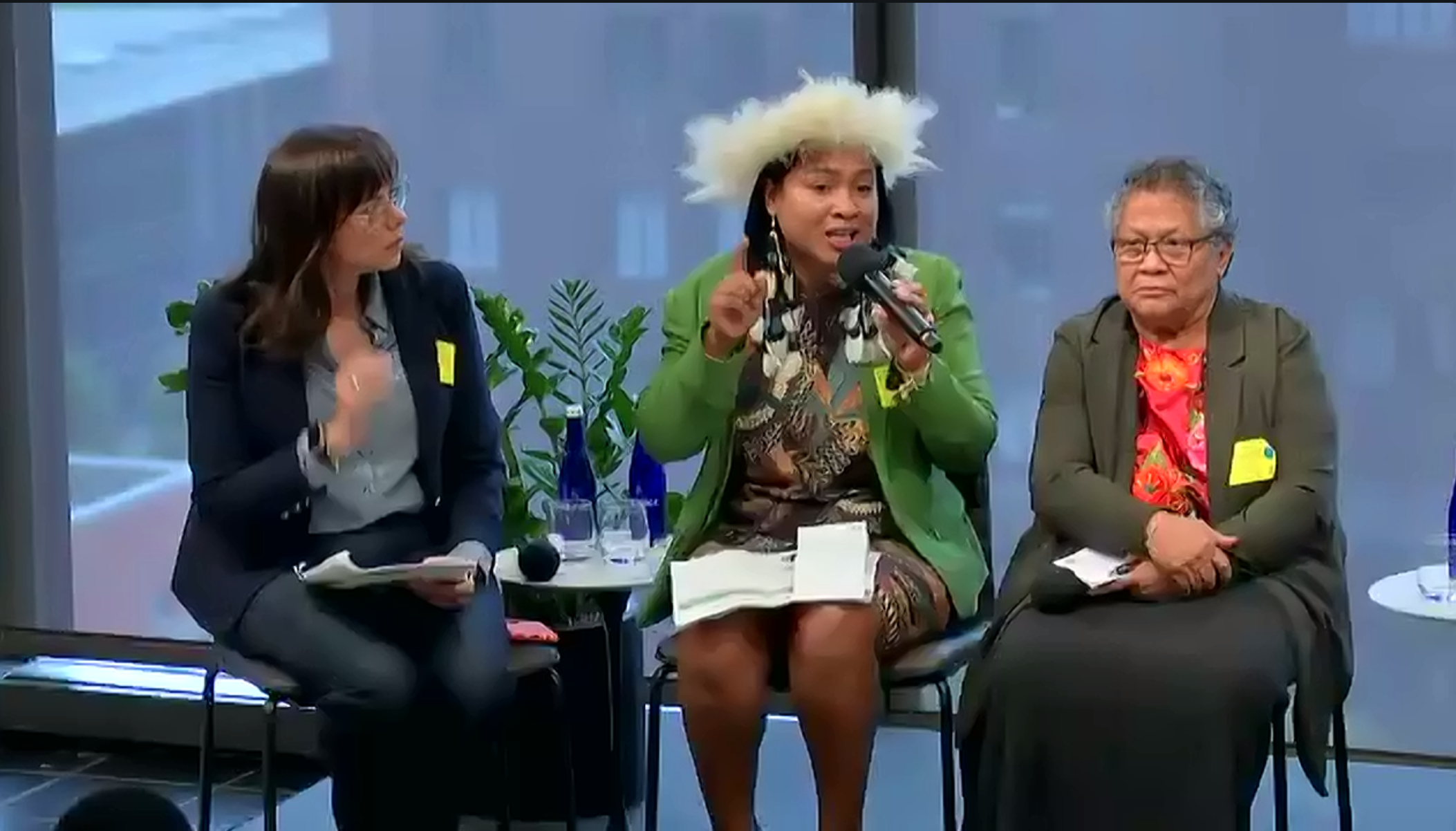

At the receiving end, Myrna Cunningham, an Indigenous rights activist with many hats, including as a board member of Tenure Facility, represented the Indigenous-led Pawanka Fund. Cunningham acknowledged the trend is in the right direction, that a lot of philanthropies were beginning to understand the need to channel funds directly where they were needed.

But she questioned why there was hesitation in giving them a real seat at the decision-making table.

“They should have confidence in Indigenous Peoples’ decisions. If we are protecting (swathes) of biodiversity, how do you not have confidence in (our) decisions?” she said.

Kimaren Ole Riamit, founder-director of Kenya’s Indigenous Livelihoods Enhancement Partners and a member of the GFC advisory board, warned again the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples as a token.

“The engagement of Indigenous People in this mechanism is not to beautify the (COP) text documents with Indigenous People-friendly language,” he said. “The idea is that self-determination of Indigenous People is in decisions and also in access to funds.”

"“The engagement of Indigenous Peoples in this mechanism is not to beautify the (COP) text documents with Indigenous People-friendly language. The idea is that self-determination of Indigenous People is in decisions and also in access to funds.” "

Cunningham said the 7 percent share of the COP26 pledge currently going directly to Indigenous funds was not enough.

“It should be at least 20 percent, maybe it should be more,” she said, adding that language about direct funding should be added to a future pledge. This should be particularly the case with a second donor agreement possible at COP30 in Brazil next year.

Whether there is enough money being directed overall to fighting climate change and protecting biodiversity was also raised.

Ford Foundation’s Walker noted that domestic and international flows from public and private resources to combat climate change, reached an all-time high of $1.4 trillion in 2022.

“That’s good news, but it’s not enough, because we know that the figures are well below the estimated $5.2 trillion per year needed to stay on track to limiting 1.5 degrees warming by 2030,” he said.

Tenure Facility Executive Director Nonette Royo moderated the Land Dialogues, which also featured Asyl Undeland, from the World Bank’s enABLE programme, Sonja Sabita Teelucksingh, adviser to the CEO of the Global Environment Facility, Angela Kaxuyana (see box below) representing Podáali, and Land Portal Managing Director Laura Meggiolaro.

This event was the first of a series of New York Climate Week moments aimed to engage multilateral funding institutions in a conversation around commitments towards the upcoming pledge renewal at COP30, including events facilitated by the Forest Climate Leaders Partnership (FCLP) and the High Level Climate Champions.

* The United Kingdom, Norway, Germany, the United States, and the Netherlands, plus the Ford Foundation, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, the Christensen Fund, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Sobrato Philanthropies, Good Energies Foundation, Oak Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and as part of the Protecting our Planet Challenge) Arcadia, Bezos Earth Fund, Bloomberg Philanthropies, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Nia Tero, Rainforest Trust, Re:wild, Rob and Melani Walton Foundation and the Wyss Foundation.

Articles