Election opens door to implementing Panama’s progressive law protecting the land rights of Indigenous Peoples

Panama’s legal framework for protecting the land rights of Indigenous peoples is one of the world’s most progressive, particularly with regards to indigenous ‘comarcas’, administrative regions with a degree of autonomy. Indigenous Peoples’ rights to land are enshrined in Panama’s constitution. Despite this, 27 indigenous communities have not yet managed to successfully complete the process for securing collective title to their lands. Threats to the land rights of Indigenous Peoples come not from the law, but from increasing competition for access to lands that are claimed by Indigenous Peoples but are not yet titled. Competition for indigenous lands comes from the private sector, the landless poor, and government claims to protected areas.

Panama’s national assembly affirmed the rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2008 when it passed Law No. 72, establishing the procedures for titling indigenous land that were left out of the comarca system. Panama’s Supreme Court of Justice affirmed again indigenous rights when it declared Indigenous Peoples have the right to occupy their indigenous lands whether or not they possessed legal title. Yet, implementation of indigenous rights lags far behind Panama’s aspirations. For decades, the central Government has emphasized economic investment at the expense of Indigenous Peoples’ tenure rights. With the election of President Juan Carlos Varela in 2014, there appeared to be new political will in Panama to make significant advances. The National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama (COONAPIP), with Tenure Facility support, is accelerating the titling of indigenous lands and building the capacity of Indigenous People to defend their rights against encroachment.

Who are the Indigenous Peoples of Panama?

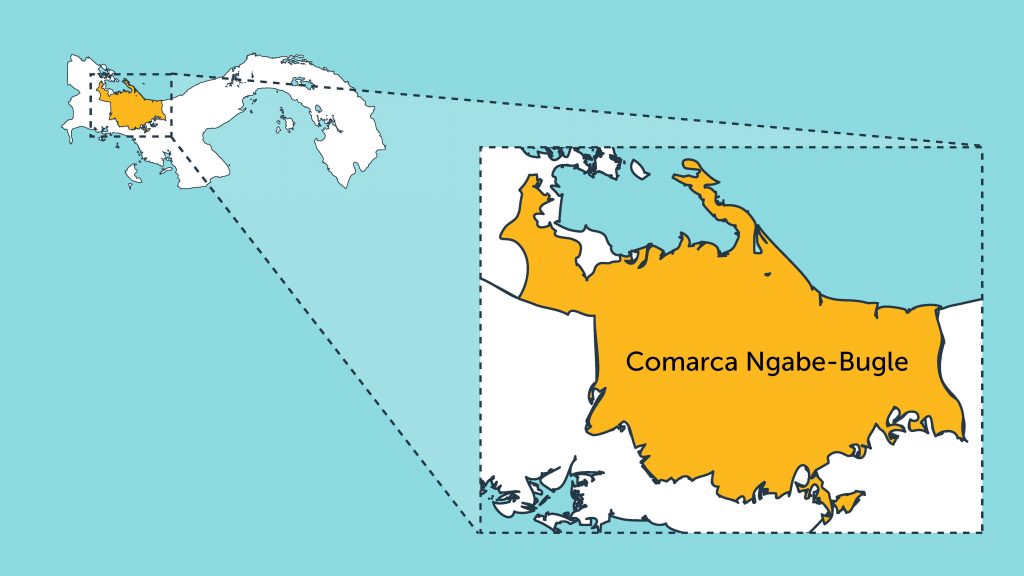

There are seven Indigenous Peoples in Panama: Ngäbe, Buglé, Guna, Emberá, Wounaan, Bri bri and Naso Tjërdi. According to the 2010 national census, they together represent 417,559 people or 12% of the Panamanian population. The Afro-descendant population, which is significant in Panama, does not claim its rights as collective subjects.

1904

1904

Panama’s first constitution allows special political territories to be established for reasons of administrative convenience or public service, setting the stage for indigenous territories.

1938

1938

Panama defines the concept of ‘comarca indigena’ as an administrative region with a degree of autonomy.

1983

1983

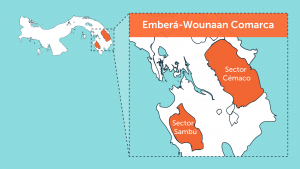

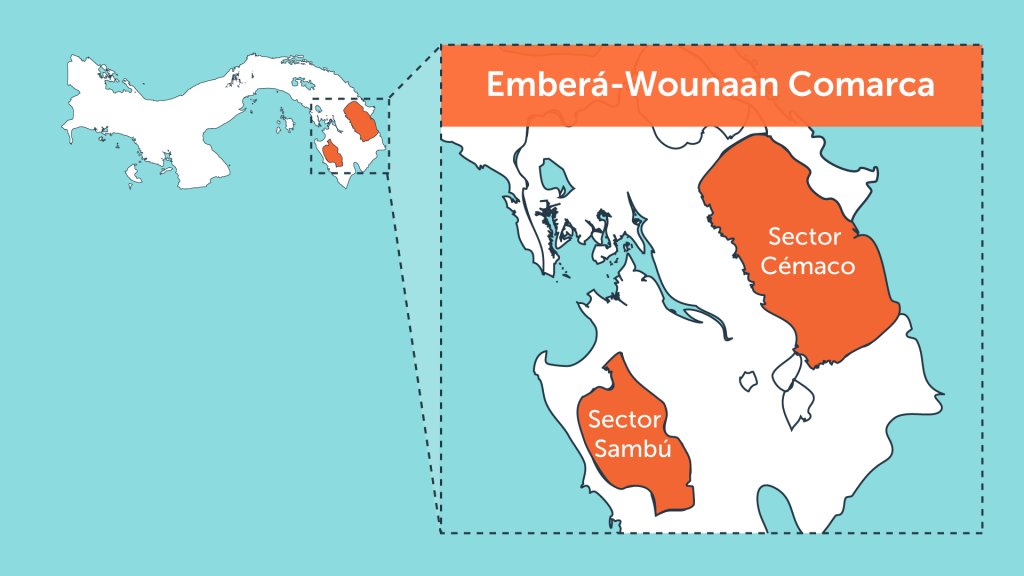

Panama establishes second indigenous territory, the Comarca Emberá-Wounaan.

1996

1996

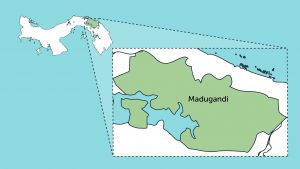

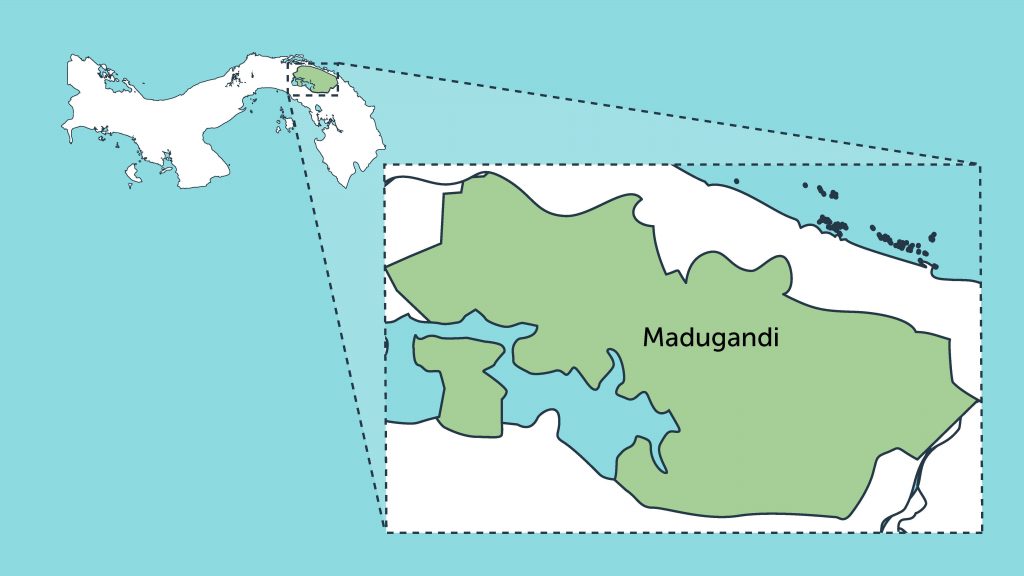

Panama establishes the third indigenous territory, the Comarca Madungandi.

2000

2000

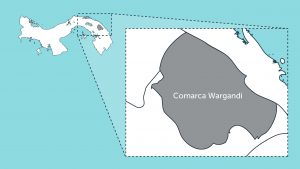

Panama creates the Comarca de Wargandi.

2008

2008

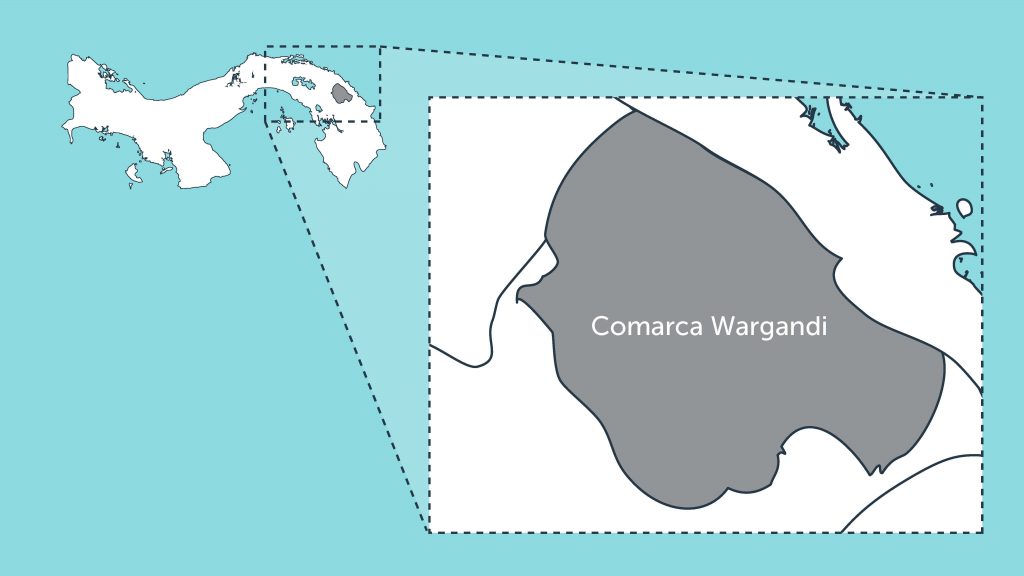

Government passes Law Number 72, establishing a process for titling indigenous lands.

The National Assembly of Panama passes Law Number 72 through which the state “shall recognise the lands traditionally occupied by the Indigenous Peoples, and shall grant to them the title of collective ownership.” The law recognises for the first time the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Panama to their lands outside the comarcas, and establishes a process for Indigenous Peoples to obtain collective title to those lands. This land title is collective, indefinite, non-transferable, irrevocable, and inalienable. Implementation of the titling process remains slow.

2014

2014

All participating candidates promise to consult with affected comarcas about investments in indigenous lands in a manner consistent with indigenous communities’ governance structures.

2014

2014

Inter-American Court of Human Rights sides with Indigenous Peoples of Panama.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights makes a landmark decision in the Case of the Kuna Indigenous People of Madungandí and the Emberá Indigenous People of Bayano and their Members versus Panama. The IACHR rules that since the government of Panama recognised the Court in 1990, it has “had a duty to delimit, demarcate and title the lands … which in many cases it has not thus far done.” While the case specifically covers two territories where resettled communities did not receive titles, the ruling sets a precedent for other territories. The ruling includes payment of damages and calls for titling of Ipeti and removal of non-indigenous colonies from Piriati.

‘The rights to use and enjoy their territory would be meaningless in the context of indigenous and tribal communities if said rights were not connected to the natural resources that lie on and within the land. That is, the demand for collective land ownership by members of indigenous and tribal peoples derives from the need to ensure the security and permanence of their control and use of the natural resources, which in turn maintains their very way of life.’

-Inter-American Court of Human Rights

2015

2015

COONAPIP engages with Tenure Facility.

COONAPIP launches the Project to Strengthen the Collective Rights of Land and Territories of the Indigenous People of Panama (PDCT), with support from the Tenure Facility. The project aims to accelerate titling of indigenous lands, resolve tenure conflicts, and develop legal and administrative capacity to protect indigenous land rights.

2016

2016

Clinica Juridica accelerates land titling.

COONAPIP launches a legal clinic in a ceremony at the Panama National Bar Association. The clinic meets a crucial need for legal support to process and defend Indigenous Peoples’ claims to land and resources. In its first year the clinic defined the ‘roadmap’ for titling in Panama, advanced titling over hundreds of thousands of hectares and increased the understanding of government and traditional authorities about titling processes.

2017

2017

COONAPIP trains 252 people in five territories on indigenous rights and law.

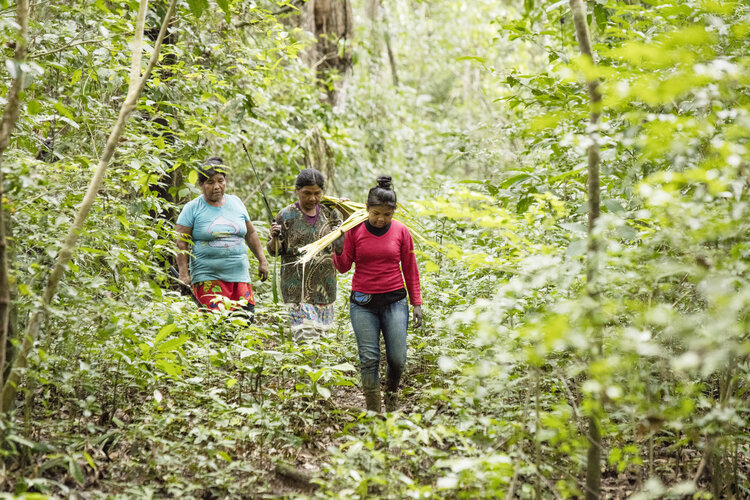

138 people in Tagarkunyala learn about territorial governance, as well as conflict management and resolution. 32 lawyers learn about the importance of the judgment of the IACHR in Bayano, and its significance for the defence of territorial rights. 24 women learn about their rights to land, access to justice and experiences of other women working to defend and govern their territories. 24 technicians and 36 indigenous authorities train in national and international legislation.

2017

2017

COONAPIP and local congresses advance titling of 231,328 hectares in six territories and resolves tenure conflicts over 223,260 hectares.

2018

2018

Panama’s recognition of Comarca Naso Tjër Di awaits presidential approval.

Panama’s Legislative Assembly approved on 25 October 2018 the creation of a new indigenous territory, Comarca Naso Tjër Di, covering 160,616 hectares in the Caribbean province of Bocas del Toro. The Assembly’s decision to pass Bill 656 came after decades of struggle by the Naso for recognition of their ancestral lands. The President’s signature is still required for ratification.

Comarca Naso Tjër Di includes two protected areas—Amistad International Park and Palo Seco Protected Forest.

The National Coordinating Body of Indigenous People (COONAPIP), with funding from the Tenure Facility, provided some technical and financial assistance to the Naso in their efforts to secure title to their lands.

“We congratulate all our Naso brothers and we celebrate with great joy this advance that only requires the signature of the President of Panama to become law of the Republic,” said COONAP President Marcelo Guerra. “This achievement is not only one of COONAPIP, but of all indigenous peoples. At last we have justice.”

2019

2019

Breakthrough resolution from Panama’s Ministry of Environment.

In November a breakthrough resolution from Panama’s Ministry of Environment recognised the legitimacy of indigenous land rights and opened the way for the land titling of 25 territories. These include the lands of the Naso people in La Amistad International Park (PILA) and the Guna of Tagargunyal, who live mainly in Darien National Park (PND). The new ruling refers to international law over national law, and regards indigenous land claims as equal in legitimacy to Western forms of property ownership.

1903

1903

1930

1930

Panama establishes its first indigenous territory, the Kuna Indigenous Reserve.

1953

1953

This law defines the rights of an indigenous territory to self govern within the nation state. Territories are called “comarcas.” They administer justice, conflict resolution, land use and bilingual education according to their own cultures.

1991

1991

Indigenous Peoples found COONAPIP, the National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama.

Leaders of seven indigenous organizations establish the first national Indigenous People’s organisation in Panama. Each member has its own culture and system of governance. Together, their territories encompass most of Panama’s forests, biodiversity and water bodies.

1997

1997

Panama establishes the fourth indigenous territory, the Comarca Ngäbe-Buglé.

2007

2007

United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopts the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

General Assembly adopts UNDRIP with 144 countries, including Panama, voting in favour.

2008

2008

Government issues first Tierras Colectivas titles under Law Number 72.

Five years after the passage of Law Number 72 establishing a process for titling Tierras Colectivas, Panama’s government issues the first three collective land titles under this law. While symbolically significant, these titles cover only 26.9 square kilometres, less than 1% of the indigenous lands remaining to be titled.

2014

2014

Forum of the Twelve Congresses and Councils of the Seven Indigenous Peoples is established.

The “United Forum” fights for the implementation of the territorial rights of the Indigenous Peoples, through the strengthening of the indigenous organisations and the adoption by Panama of the Convention of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of 1989, known as ILO Convention 169. This is an important binding international agreement on Indigenous Peoples, precursor of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

2015

2015

Supreme Court of Panama rules in favour of the Arimae and Embera Purú and they receive title to their lands.

2016

2016

Panama adopts Law 37, requiring free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples when legislative measures could affect their collective rights, physical existence, identity, quality of life or development.

The text of the Law establishes Panama’s obligations for districts, annexed areas, collective lands and ancestral lands.

2016

2016

COONAPIP maps land invasions in the Embera Wounaan Comarca with fixed-wing drones.

2017

2017

Faculty of Law at the University of Panama prepares to offer new diploma in legal administration and organisation of territories within the framework of indigenous rights.

COONAPIP progresses with the Faculty of Law of the University of Panama in efforts to establish a Diploma in legal administration and organisation of territories. The aim is to increase knowledge about national and international legislation that protects Indigenous Peoples.

2018

2018

With a clear roadmap for titling, experience, and momentum, COONAPIP scales up efforts to secure indigenous territories and build capacity to govern them.

COONAPIP launches the Tenure Facility-funded Project to Strengthen the Territorial Security and Organizational Capacity of the Indigenous Peoples of Panama. It aims to secure collective title over almost 200,000 hectares, working with the residents of up to 12 indigenous territories and government. These claims include those blocked because they overlap with areas designated for conservation. The initiative will strengthen communication among indigenous authorities and with government and the public, and build the capacity of indigenous women leaders.

2018

2018

President Varela vetoes Bill 656 citing unconstitutional conflicts with protected areas in La Amistad International Park and Palo Seco Protected Forest.